How the Flames of Gal Blazed Forth

How the Flames of Gal Blazed Forth

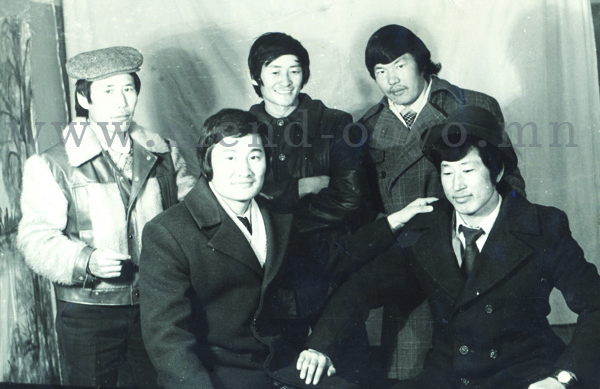

G.Mend-Ooyo

During our time as students in the 1970s, our close group of friends created the Gal group based around our common interest in poetry, and it is true that we, with our youthful desires, would come to create an era in the history of Mongolian literature. We first made friends in class, during 1974 and 1975, and on 8 November 1977, we initiated the secret literary group Gal. The social system at that time meant that we had to keep ourselves hidden, away from the legal framework regarding the establishment of groups. About the establishment of Gal, Ü.Hürelbaatar has written a great deal. While everything was overturned during the 1990s, the members of Gal remained loyal to one another, and so we have reached the present day through generously dedicating the valuable time of our lives to one another in friendship. We lack for nothing. But there remains a wonderful story of how we focused together on the great work of literature. When we meet with our readers, they are interested in what Gal is, who are its members, and so I would say a few words about how those young men of literature flourished. These were the flames of the fire, the flames of Gal.

During our time as students in the 1970s, our close group of friends created the Gal group based around our common interest in poetry, and it is true that we, with our youthful desires, would come to create an era in the history of Mongolian literature. We first made friends in class, during 1974 and 1975, and on 8 November 1977, we initiated the secret literary group Gal. The social system at that time meant that we had to keep ourselves hidden, away from the legal framework regarding the establishment of groups. About the establishment of Gal, Ü.Hürelbaatar has written a great deal. While everything was overturned during the 1990s, the members of Gal remained loyal to one another, and so we have reached the present day through generously dedicating the valuable time of our lives to one another in friendship. We lack for nothing. But there remains a wonderful story of how we focused together on the great work of literature. When we meet with our readers, they are interested in what Gal is, who are its members, and so I would say a few words about how those young men of literature flourished. These were the flames of the fire, the flames of Gal.The flame of Bat-Ochirin Sundui (1954-1993)

The person who beat the drum with his poems was B.Sundui.

As the gooseberry grows to a fluffy fathom’s length when ripe,

the spirits gather in my mind of eighteen years for no good reason.

Once I find the thoughts I’ve written down, they’re already right –

surely I haven’t lost those bones of mine, those fine poems?

This work, “The Poem I Never Got Round To Writing,” both carefully wrought and written with a combination of melody and meaning, was something we read aloud, it acted at that time in our young lives as a kind of poetic propulsion. It was almost too much, given his youth, it was dense and meticulous, fresh and elegant, his poems seemed really to be under someone’s control. Sundui was a model for writing faultless poems which possessed meaning and melody and rhythm. Unfortunately, only his first book, Balj’s Young Cherry Tree, was published. His second book, Bright Distance, had only just reached the publisher when he passed away into the bright distance himself. By chance Ü.Hürelbaatar found this book, and now it is ready for publication. Although we are ready to prepare his third book, it will require effort and time to find and collect the poems. He concluded his legal studies and became well-known to the world of literature, and while he was accepted into the Gorky Institute of literature, he simply came back from Irkutsk, where he was preparing.

Saruulbuyan, Sundui and I traveled together to his native hearth, along the Herlen, through Ereg Büüleg and Gurvan Baidilg in the area of Möngönmorit, and there we met with his mother in a seniors’ home, and on the way we went to the great Natsagdorj’s birthplace at Gün Galuutai. The five days we spent traveling are now very clear t my mind,

Though he performed his duties as a newspaper correspondent and a peripatetic investigative journalist, truly at the core of his heart he was an accomplished poet, with no concern for anything except for poetry. And now, Sundui, who led our caravan of the 80s generation from the front, has entrusted to his own generation the completion of that poem he never got around to writing, and he is famous in Heaven.

The flame of Dagvadorjiin Tsogt (1952)

At that time, I certainly never saw anyone reading so much as D.Tsogt. He read straight through the classics. And he talked with his friends about what he had read. Our great teacher B.Yavuuhulan thought highly of him, and kept the manuscript copy of Tsogt’s first book, Song of the First Furrow. One of his first poems was “Jargalant River,” and this poem is about how, with the bright yearning of childhood, he set his paper sailing ship upon the waters of the river, and about the hero who sailed in it around the world. When I think about Tsogt, this poem always comes into my eyes:

On the infant white voice, the milk had been sipped,,

the evening sky quenched its thirst and brightened.

The song fluttered in the heart, and the sun burnt

through the restless boy’s thin shirt…

In fact, this boy, whose heart the song sent fluttering, who could no relax, and through whose shirt the sun burnt, was the poet himself. He thinks very precisely and clearly, he expresses his ideas honestly, consider them for a long time, he writes rarely, and what he writes is spoken from his very bones. O.Dashbalbar wrote once that Tsogt was the most influential of our generation, and proclaimed him the “student leader.” He calmed Dashbalbar down, who was proud and hated to give way to anyone, by showing him the future with just a few words;

When there are stars,

remain clear!

Tsogt became a skilled surgeon, and the time which he otherwise would have used in making a collection of his work he used in saving people’s lives. In 2002, however, his second book of poetry, The Continuation, was published, the name referring to it’s being the continuation of what had gone before and what would continue afterwards. Soon, his novel The Surgeon reached his readers, and not only did this reveal our Tall Tsogt as a man of high learning, but as a something remarkable in literature, and which will continue.

The flame of Tseveendorjiin Oidov (1953)

Nature bestowed upon him an unusually singular skill, a complex character, and an outstanding and sharp intellect, and at eighteen he began straightaway to create art of extraordinary genius. He made a wood-carving, called The Experienced Herder, and this was installed in the Museum of Representative Art, even though what he had created during those difficult times was an image of Chinggis Haan. Unfortunately, this piece was caught up in a fire which swept through the museum. He has created representative works of almost every kind – carvings, paintings, monumental ornaments, graphic design and cartoons. In 1992, Oidov had the rare good fortune to create the Mongolian State Emblem and the State Seal. Although he writes in most literary genres – poetry, lyric, short stories, novellas and novels – it is curious that these have not been published. At the time when there was no scent of modernism in Mongolia, he brought forth genuinely modernist poems. In 2008, he compiled a nine-volume book of his writings, Blue Mongolia’s Epic of Jade, of which the first volume, The Sky’s Fair Complexion, brought together examples of his reworking of the traditional hos uyanga (picture and poem) form from the 1970s and 1980s, but this has never made it to the bookstores. Oidov’s hos uyanga are highly individual. These jade aphorisms are four-line poems of melodious wisdom, with a drawing expressing the music of the intellect. Having brought the picture and the poem together, he deciphers and divines the wisdom held within the work. And so it opens. On the one hand, Oidov’s first volume is an art catalog, and on the other hand it is a volume of poetry. The two are brought together as a mirror of divination. Oidov’s pictures are brought to life through jade, and his line gives melody to the poems. And the musicked line creates a living world. The pictures discuss poetry, the poetry discusses the pictures.

I am the seven silver eyes who spend the day in the place of honor

in the sky.

I am the stars which come together in melody on the two strings

of the horsehead fiddle.

I am the grasses bending towards the planets, kissed by the rain.

I am the soul of the poetry of the ancient ones, which dwells in the love from which I fled.

Such is the nature of his poetry. And if you ask him, Why did you not hurry more? he has but one answer: “Because my life has been spent creating images with brush and ink. I have lived together with the years as they changed and passed me by.”

The flame of Yadambatin Baatar (1957)

If there is an unsolved riddle, an unknown world, it is Ya.Baatar. When he entered Ulaanbaatar College having finished tenth grade, he didn’t write traditional Mongol script badly, he had assembled his first book of poems, and he completely understood The Ocean of Stories and the Gesar epic. He is a rare person, one who has read classics such as these, and who has grasped that these texts form the cultural heritage of his people. He is in no hurry to publish. He studies. In fact, study is his special quality. It’s not that he doesn’t have enough work already which he cannot complete, correcting the errors in the selected texts for books of senior writers and in the collections of poems by writers like ourselves among his own generation. That in itself requires studying. But he is in no hurry to publish. If you ask him why this should be, he has but one answer: “A man’s nose grows throughout his life.” His first collection, The Mountain Slopes Are High, brings together poems written since he has been living in the United States, and last year he published The Mountains, More Tranquil Than The Slopes. The names of these books, we might say, deal with the dimensions the relationships of existence in this world, and Baatar confirms this with his idea that “A man’s nose grows throughout his life,” perhaps he is getting rich with thoughts about adding a couple of meters to Everest, to the roof of the world. Baatar’s approach has grown over time, this is the general rule of his literary work. He has said that, during the nineties, he put together the first of ten volumes, but now there are more than ten, with novels, novellas, poetry and scholarship. Baatar is an example of one who hides his light away.

Baatar is acclaimed for his long historical essay Gombojavin Mend-Ooyo, the 47th volume of the series Twentieth Century Mongolian Writers, which is the most extensive overview of my own work.

He had a close relationship with the great writer B.Yavuuhulan. But he never exploited the fact that Yavuu was his uncle. But he compiled three books of Yavuu’s work, and four books of research about it. But the man who studied and revealed Yavuuhulan in this way still does not exist. Sadly, these books have never been published. Baatar has discovered that the three hundred and sixty words of Yavuuhulan’s famous poem “Where Was I Born?” symbolizes the Mongolian calendar, with its sixty lines as the sexagenary cycle, its twelve verses as the twelve lunar months. And so there’s a new thought growing now.

The flame of Lamjavin Myagmarsüren (1957)

At first he wrote long poems, clear as the most accomplished pictures of our flourishing generation.

I make an offering to Tenger of loveliness,

deceitful in its truth, as when the moonlight touches crystal.

I split the pillow with you, my desire to stroke your hair delayed,

edgily I smoke beneath the window,

my shadow gets bored of me, and makes friends with the darkness of night…

His poetry shines like crystal dust among out generation. This golden young man glistened like his poetry, his singing was like untuned music, and oh, the gentle winds of autumn overflowed with melody as though they were tuning the grasses. Myagmarsüren is an unusual person, he feels everything clearly, and he crafts his poetry with an awakened sensibility. His first collection, Birds of Passion, and it seemed that his youthful poems had come flying in like true birds of passion.

The infant shoots emerge,

tickling the sun’s feet…

And verses such as this came flying in with those birds of passion. Once he had finished medical school, he directly took up not a stethoscope, but a pen, and he came before the golden microphone at Mongolian Radio and wrote poems for broadcast, and so began his life of two jobs. He has never struggled to find any other work.

Myagmarsüren has always been loyal in his relationships as pupil and teacher. He held his two teachers, M.Tsedendorj and N.Nyamdorj, in great respect, he cared for them, and shared in their unhappiness. From the time that his first book was published and he began to be known, Yavuu’s wife Adiya summoned Myagaa back to care for Yavuu, and he came running. And he likes to remember how, around the fire in the hearth of our great family of Mongolian Radio he raised N.Myatav, D.Hasbaatar and De.Myagmarsüren with love and kindness in the work of literature.

Baatar, Oidov, Tsogt, Myagmarsüren and myself began, during the 1990s, to publish a newspaper called Gal (Fire), but this ceased production after only four editions. We still have a yearning to publish a magazine later, and a greater wish to publish an anthology.

The flame of Shagdarsürengiin Gürbazar (1955)

Before he was accepted into the National Teachers’ College, his exceptional ability was clear. It seemed that this child who wrote poems and plays and lyrics was the boss of our circle.

I well remember the times which really glistened with his warm heart and his fanciful spirits. We would take the mediocre poems which had been read in our circle, and wander around the universities and medical colleges, tearing into them. Güree would read his poems first. He would search for an especially interesting thought. We would praise a poem of Güree’s, about how, when money falls, so upon it do eyes fall, and with the eyes of many people their legs step forward, and we all set out to discover thoughts as especially sharp as this. His first book was Festival With Wheel Patterns. The wrestlers shake the mooncake patterns on their jackets into ovals, the children trot the wheel patterns on their deels away, and the wheels run along the horses’ tracks in the ground. These lovely poems show, in these images of the Mongolian naadam festival, the nomadic worldview and a deep pleasure in beauty.

Many of Gürbazar’s songs are expanded versions of the kind of songs people enjoy hearing, but they have yet to come down from the stage to be read as the exceptional poetry they are.

I believe it was New Year’s 1976. I am thinking of how we were in Güree’s wages office in the 19th district, jumping up and down and singing, piling up an excess of Bengal Fire firewood and setting fire to it, and we were shouting, “Let the fire burn!” Güree was against the establishment of Gal, he seemed cautious, he said, “It’ll certainly hurt our friendship.” However, he was one of the first members of Gal. Suddenly, Güree was the director of the Writers’ Union’s Children’s Story Room, he was working for Mongolian Television, he was acting in films, and galloping here and there through the evening game shows. So he had left us somehow.

As I see it, he doesn’t like to remember Gal. Perhaps his new field has something to do with the fact that our expectations did not fit together well.

The flame of Jümpereliin Saruulbuyan (1957)

He began by drawing cartoons, and then he decided that he would work on lyrical sketches and book design and portraits and fine art, and so he fell in with us.

The sun leaves the sky behind,

the yellow of the leaves

turning copper red as its sets…

Yavuuhulan thought highly of these lines, and even more he cradled the book of poetry in which it appeared. There is no separation between Saruulbuyan’s pictures and his poems. As O.Dashbalbar wrote,

What Jümperei’s son Saruulbuyan draws,

the orange sun turns to red on paper…

He got a job as a theatrical set painter and, seeing that its power was equal to literature and representative painting, he found in them the theme of his research, and he wrote his doctoral dissertation about the depiction of horses. Horses and wrestlers are his eternal themes. He’s written many books too. Saruulbuyan is indefatigable. If you were to say, Name the craftsman who has done most to honor the heritage of the ancestors, to learn from it, and to carry it forward in time, that would be Saruulbuyan. “The Herlen is Serene” bars witness to this. He writes and draws and studies in a straightforward fashion. He has written about history, race, archeology, art history, humorous art and cartoons, and fine art, as well as about all genres of literature. His writings are well-researched, thorough and serious. They withstand the test of time. Saruulbuyan is one of the most eminent writers of his generation.

The flame of Ürjingiin Hürelbaatar (1954)

Ü.Hürelbaatar’s is an influential name in Mongolian literature, journalism and theater studies. When, during his student days, he began to write criticism, he worked as a theater critic alongside the esteemed art scholar S.Luvsanvandan, and wrote his doctoral thesis on the work of D.Namdag. “Namdag Studies” comprises both theater studies and literary studies. He has an innate skill for studying, compiling, and critically refining. When I was at Mongolia Radio, I brought members of the so-called “golden generation” – E.Oyuun, D.Chimed-Osor and D.Namdag – and put them in the studio for a discussion. As well as publicizing this event, his work was also to study it. He went to the Mongolian Radio’s golden fund for the money to write about this extended discussion between these great names in Mongolian literature. The literary scholar Ts.Mönh brought Hürelbaatar to her office, and D.Namdag pulled him into theater studies, and it was he who brought the Gal group from here and there and gave them this and that and tuned their poetry.

The years when he worked as editor of “Ulaanbaatar” newspaper were perhaps his golden years. This newspaper was published in editions of thirty-two or sixty-four pages for a substantial readership, and it made a substantial contribution to the democratization of Mongolian society. The wrestling matches featuring the upper echelons of wrestlers, the lions and the eagles, as well as other competitions were reported in the paper, and so the reputation of journalism was elevated. He initiated the leading article, “A Line From the Editor,” which summarized as fully as possible the political and societal concerns, and these articles showed the kind of journalist, researcher and writer he was. He also revived the culture newspaper “Art and Literature,” which had suffered along with the financial markets, and later he passed it over to those of his own generation.

Hürelbaatar is responsible for the study, research, archiving and annotation of the Gal group, and he wrote an essay, “How the Underground Group Gal Came To Be Established,” based upon evidence from his archive.

Hürelbaatar has written poems under the influence of his friends, and in recent years, having published a book of these poems, Metaphors For the Earth, he has been writing haiku, which have been acknowledged by the Japanese Haiku Society, such as this one:

Silence midday autumn,

the sun resting, the leaves asleep,

the clouds smiling in slumber.

There is no doubt that he is nowadays the one leading the way in discussions of the poetry of song.

Hürelbaatar has a large archive. And as much as, for thirty or forty years, he has been archiving and writing about Mongolian theater studies, literature studies, journalism, and the important curators, writers and researchers of his generation, so he has also been acting as his own archivist.

The flame of Ochirbatin Dashbalbar (1957-1999)

The seventeen-year-old boy from Sühbaatar aimag who sought us out is the now famous poet O.Dashbalbar. When he was collecting books from Baruun-Urt, some of them had become food for the marmots, and so he put together a sack of new books and handed them out to the people in the town. Meanwhile, he had became M.Tsedendorj’s student and the head of the Organization for Youth. He met with L.Tüdev and took a position at the new library, and he made it known that his plan was to write a novel called Youth. We in Gal needed to develop a strategy. Tüdev was a smart man, and knowing that so proud a poet would be killed if he went where those young people were, he got him work in the town’s committee and set him on his path. Gal began gently to prepare him for the Gorky Institute. Within our family we looked after him. As Tsogt wrote in a poem,

Our new member O.Dashbalbar

has chosen to take a job,

making his bed on the floor…

That Dashbalbar became a student at the Gorky Institute was his rare good fortune, but for a member of Gal it was a lucky break. He would take our poems, make parallel translations, discuss them in his poetry seminars and send back letters about what had been said. So it was that Gal supported the opening up of Dashbalbar’s world. He wrote extensively about this, about how my parents-in-law’s parlor in the Textile District became the General HQ for Mongolian poetry.

Although the first poem in every one of his books was “My Life In the White Grasses, Faded By the Wind,” although it was “Love One Another, O My People! Which made his name, and although his song “My Country And I Have Been Waiting For Our Ancestors, We Are Expecting Our Descendents,” all of his poems were written under the influence of Gal. Dashbalbar set light to the poetry which was inside him about the focus and the glory of his countrymen, it blazed forth and, as Tsogt clearly stated at the very first meeting of Gal, his was the genius of Mongolian literature.

The flame of Danzangiin Nyamsüren (1947-2002)

Once Dashbalbar had found his place within Gal, he brought along D.Nyamsüren, who was living in Ereentsav on the far eastern border with the Soviet Union. Nyamsüren was accepted into Gal on the strength of only a few poems, such as “The Waters of the Great Herlen” and “Poem On A Bright Morning.” Day and night he would go home and read and listen to poetry, and would come back to us with notebooks full of his poems. So the history of our literature bore witness to the development of this provincial poet within Gal. He was fresh grass from the smokeless wilderness, he didn’t wash his head with all those “isms” in poetry, he didn’t know about western movements and trends, he received his nourishment from the clear bright melody of those of his generation and developed himself as an exceptional Oriental poet. But he wasn’t only nourished on poetry, he established himself on the pure bright path by taking pleasure in study, by working on his mind and body, and by contemplating the magic of words, and all this was opened up to him by Gal.

The Four Seasons was a strange poem of twenty lines or so. Gal suggested that he extend it to the length of D.Natsagdorj’s “The Four Seasons,” and with great acuity he did indeed extend it and greatly improved it.

It’s not that those who honored and followed Nyamsüren think of him as a poet drunk on the gods’ nectar it’s just that they don’t know the secrets of how he was drunk on the Buddha. There is meaning in what he wrote, that “When I am old, poetry will make of me a reincarnation.” When he heard I was in hospital, he wrote a beautiful poem in a letter, words which soothed my mind:

Let the eternal sun shine through the window.

In an instant let your exhaustion be cleared away…

Nyamsüren wrote letters to the members of Gal from the countryside. His letters were like poems, with their magical words, they were as peaceful mantras to soothe the mind.

Dashbalbar read his poetry from the platform of Writers’ Congresses and Conferences, and in 1991 he wrote an essay, “The Nature of the Mind, or Danzangiin Nyamsüren,” which introduced Nyamsüren to the world of literature, and here he declared, “Though I want to say both that he is and that he is not at the level of Ravjaa, Natsagdorj and Yavuuhulan, we should agree to take the time to wait.” Though we flew upwards towards the golden regions, coming together as a group and encouraging one another, we didn’t esteem him as we lent one another support, and now he has been taken away.

The flame of Jamsrandorjiin Oyuntsetseg (1951)

J.Oyuntsetseg is a soft and melodious zither playing in our time in the gardens of poetry. It was Sundui who brought her to the literature group at the Mongolian National University, thinking to get to know this woman poet who was doing so well for herself, working in the post office, and with her poems appearing constantly in the pages of the newspapers.

A single teardrop of rain

reflects the colors of the sky.

With lines such as these, her poetry - “her genius a Buddha brought to life” - inspired us, and so we became close friends.

Oyuntsetseg’s poetry has gentle and melodious strings like the zither, but it is also straightforward and resolute and virile. She became for us a fabled figure, a student in the Mongolian literature and language class who took great pains to learn Russian and Japanese, to make translations and to develop her academic abilities.

Oyuuntsetseg’s first book was Flower Petals, and another collection appeared later, The World’s Beautiful Girls. The title poem of that second book became the lyrics for one of Mongolia’s most popular songs, composed by G.Nasanbuyan. After graduating, Oyuuntsetseg worked for the Party’s youth newspaper Zaluuchuudin Ünen, and then swiftly went to work in Moscow for the famous publisher Raduga, translating the most popular Russian children’s books into Mongolian. For me, Oyuuntsetseg’s small volume of translations of haiku by the Japanese poet Basho, Not A Flower Like It, is a glittering pearl among the translations of his work. At the turn of the century, Oyuntsetseg left to study English in the United States, and is now translating and sending us the poetry of well-known English-language poets. So our quadrilingual friend has taken her poetic skill and mastery of the Mongolian language to a new level, becoming a poet engaged exclusively in the translation of poetry.

Oyuntsetseg, then, whose name means “flower of wisdom,” is indeed a flower, growing clear like a white mountain, an eternal symbol which has never been frozen and blighted by the mistaken idea that a woman might not have what it takes to do the work of poetry.

The flame of Gombojavin Mend-Ooyo (1952)

I have been close for some forty years with these loyal literary friends, we have created a history of supporting one another, of raising one another up, of developing together and of nurturing one another’s work. We have already reached our own high points by moving upwards with our joint focus, with nobody retreating and nobody losing hold of that focus. Gal embodied poetry with its one-pointed mind and, because of this, we improved ourselves, we opened up every opportunity for our intellects, and we dedicated ourselves to what our Mongolian people’s valuable culture had created, and from my point of view this has all yet to be completed.

When we look down from the high vantage point of time, although many things are missing, there is more of what we have in fact achieved. Gal did not only create a history of personal friendship, but also a history of our own path through the world of literature, our rich heritage, the lessons we learnt and the experiences we had. And while we had our own objects of intellectual worship, our own teachers, and our own education, nonetheless we set a example for one another by learning not only from those on a higher level of us but from all those around us on our own level.

Our passion was to write poems, to purify ourselves, to study without ceasing, to seek…but my faraway wish was to reach my own peak, to reveal my Mongolia to the world…

Dashbalbar, the glorious twentieth century patriot, the young prodigy, the educator, the poet who mastered time, and the exceptional poet Nyamsüren , who spanned the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and was acclaimed as the “Oriental,” by being admitted into Mongolian society, were born from the ranks of Gal. Oidov created the Mongolian State Emblem and State Seal. Baatar, Hürelbaatar and Saruulbuyan defended their doctoral dissertations, Tsogt is one of Mongolia’s finest surgeons. Four members of Gal have been named Outstanding Cultural Figure, one has won the State Poetry Prize, and two have won the Natsagdorj prize. We have not acted so as to be famous, but such are the indicators of our abilities as a group.

Now we are collecting together Sundui’s heritage, and we will soon publish a book. So we still haven’t expanded Gal, and neither have we tightened it up.

This fire which is Gal blazed from the hearts of poets, it will not be extinguished after us, and so though our collective resolve we will realize our destiny.

9 March 2013

At the center of the four mountains